Linda Stufflebean, blog author from the website Empty Branch Family Tree has shared this blog with us as part of our “How I Solved It” Series.

Linda Stufflebean, blog author from the website Empty Branch Family Tree has shared this blog with us as part of our “How I Solved It” Series.

This blog explains how the author traced the birth records of an ancestor that was born in a hospital for single mothers in Denmark and the research and travel involved to locate the information to solve her brick wall.

Do you have a brick wall ancestor, born in Copenhagen before 1910? You have a name and a birth date and the city of birth, but no baptismal record and no parents’ names? This, in spite of the fact that Danish baptismal records are quite well indexed on FamilySearch and the Danish National Archives offers their digitized church and census records online for free? This was exactly my predicament and the answer to my brick wall might be the same as yours:

Me at the Entrance

Source: My Personal Photo Collection

What is this building? It’s Den Kongelige Fødselsstiftelse, still standing today at Amaliegade 25 in Copenhagen, Denmark, otherwise known as The King’s Hospital for Unwed Mothers, established in 1785. Although the hospital is now an office building, its records still survive today.

Have you considered that your brick wall ancestor might have been a child born out of wedlock at this hospital and then given up for adoption or sent to the Copenhagen orphanage?

I was at my wit’s end searching for the baptismal record and parental names for my Johannes Jensen, born 27 April 1810, until the pieces fell into place in his military record. I have told his story in some of my earliest blog posts, but since then, I have seen various queries online from people looking for information about their brick wall ancestors in Copenhagen.

Most of the records of Den Kongelige Fødselsstiftelse are accessible by the public, as Danish privacy laws restrict them to 125 years so those up to 1892 should be searchable.

Exactly how does one search these records. Well, there are several important things to know:

First, and most important, was that the mother could choose to remain completely anonymous. That severely limits the ability to find further information.

Second, in support of this privacy, there were TWO sets of records kept. One listed the births of the children by date, but no surnames are recorded. Therefore, it is imperative that you have an exact date of birth to have hope of finding your ancestor. For example – you want to find the baptism and parents of Anna Jorgensdatter, perhaps born in January 1850. If there were six babies named Anna born in, say, January, it will be quite expensive and possibly unfruitful to find more information and I will explain why in a bit.

Each child’s record had a coded number assigned to it. That coded number is the number of the mother’s file. The mothers’ files are the second set of records.

Can you see why this gets a bit complicated?

Third, the infants’ birth registers have been filmed and are available digitally on FamilySearch. Go to the collection: Denmark, Church Records,1484-1941, then Sokkelund and choose Den Kgl. Fødselsstiftelse. From there, search by date as you normally would for any vital record. Records from 1807 to 1901 are included. This collection can also be found for free on the Danish National Archives website, but, for those who don’t speak Danish, FamilySearch is easier to navigate!

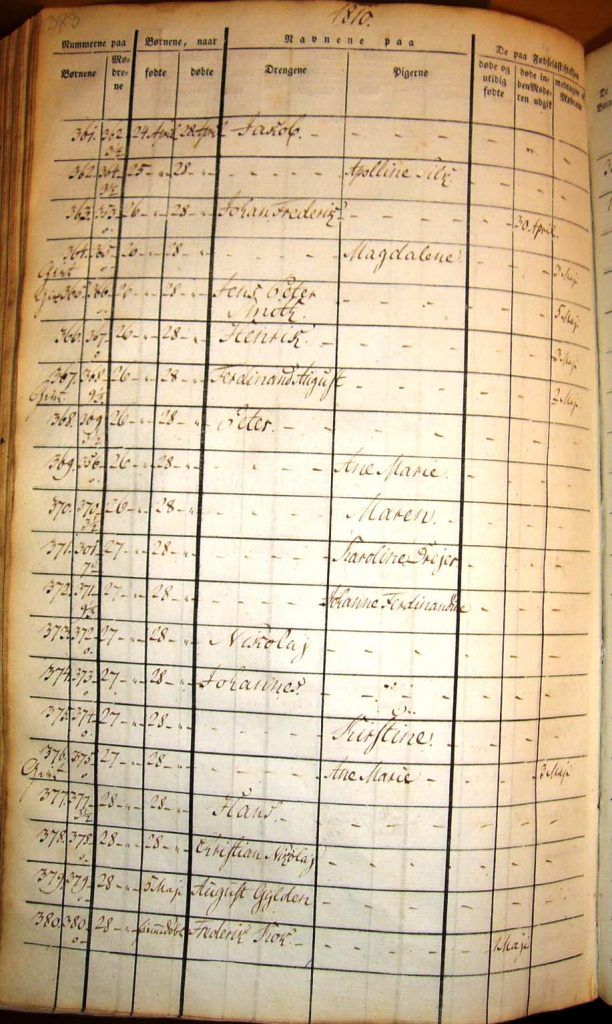

Here is a sample page from the birth/baptismal book:

Johannes, born 27 April 1810, #374 on the right

These entries were made on 28 April 1810, as seen by the heading. My Johannes has the red arrows highlighting him. Notice #374 at the far right side of the page. That is a finding number. Some babies were given only a first name, while others had first and middle names. That can help you in your search. My Johannes ONLY appeared with a single first name and no middle name in all of his military and census records.

Fourth, and here is where it gets tricky and expensive – The mothers’ records have NOT been filmed and they must be viewed in person at the Danish National Archives in Copenhagen. I had gotten this far and was desperate after years of searching to be so close, yet so far away from answers. I happened to be at the Family History Library in Salt Lake City when I found this birth record. (Six years ago, when I found it, these records were only on microfilm.)

I had previously used a professional researcher in Denmark and he did good work so I emailed him from Salt Lake asking if he would be able to go to the archives that day to retrieve the folder, copy it and email it to me. That way, I would have help reading it. The next morning, I had the images in my inbox, but it cost me about $150. Danish researchers don’t come cheap! On the other hand, what would it have cost me to travel to Copenhagen from Tucson to obtain it in person???

Before I share the record, I want to reiterate that it is very possible that if you take this step, your record won’t have any mother’s name in it or any other personally identifying information. If the mother gave her baby up for adoption, it may give the name of the family who adopted the child.

Having said that, you might strike gold as I did. My Johannes’s record, I’ve been told, is very unusual because while the first entry in his mother’s file gave no real information, a SECOND entry was made ten years later. That was apparently extremely rare. It’s also a good thing I was in Salt Lake because it took four of the Scandinavian experts quite a bit of effort to decode the writing.

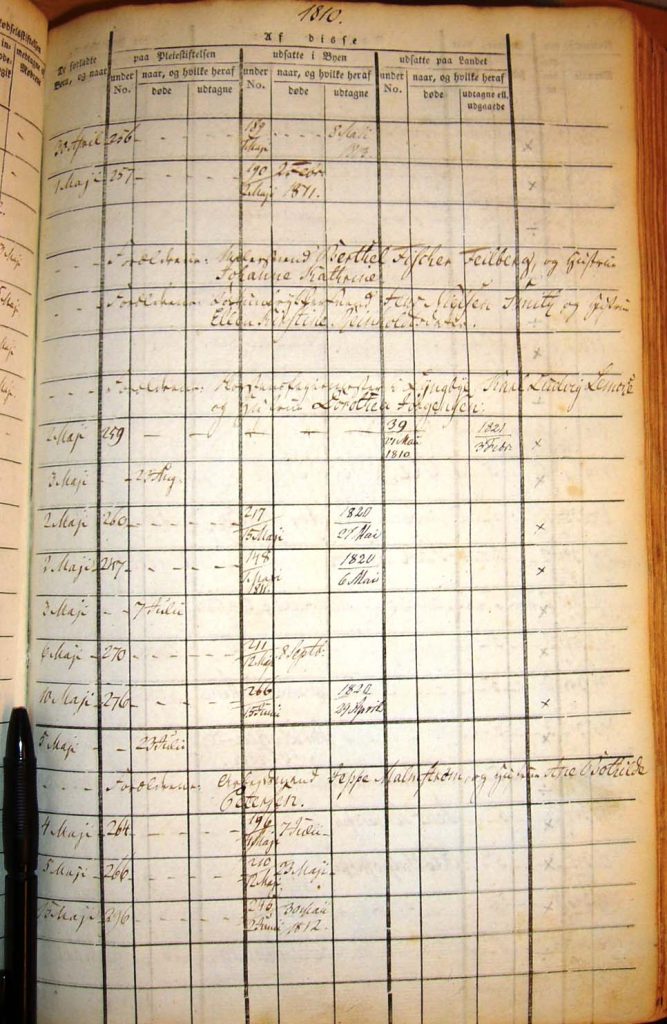

#374, Johannes

This register page ties baby Johannes to his mother and notes that he was born on 27 April 1810 and baptized the following day. It was Danish law at the time for all to be baptized.

The second part of his mother’s file is the important part:

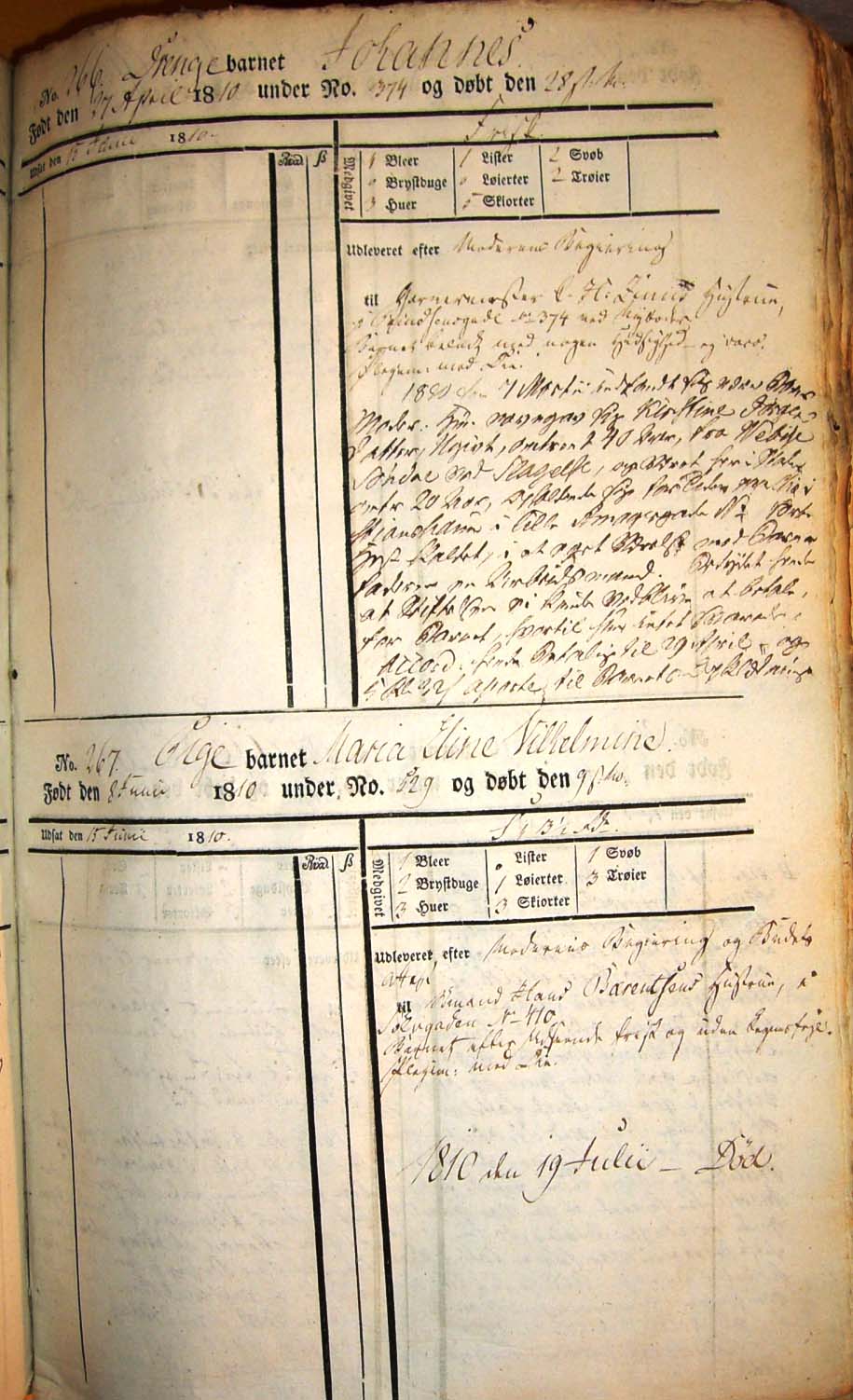

Johannes’ Mother in the Top Entry

When he was born, Johannes’s mother chose to be anonymous. Baby Joannes was given to the Master Tanner Zinn’s wife, most likely to be raised and eventually taught the tanning trade. (However, Mr. Zinn died about five years later. I suspect that Johannes was then sent to the Copenhagen Orphanage, although I can’t prove it. He would have been confirmed while living there and there is a gap with a record loss for the years when that most likely would have happened, but I digress.)

In 1820, a second entry was made in this file, giving his mother’s name – Kirsten Jorgendatter – her age of about 40 years, the information that she still lived in the neighborhood (Vor Frelser Church parish) and was currently living with the baby’s father (!) who agreed to provide a suit of clothing for him. It also said she was from Slagelse. I have since been able to identify both his mother and his father – who actually got around to getting married in 1824 – because of the information in these records.

So, the lesson here is that if you have an ancestor who might have been illegitimate and born in Copenhagen AND you have an exact date of birth, it is quite easy to search the Den Kongelige Fødselsstiftelse records to see if a child by that name was born on that day.

If you do find a possible candidate, you’ll need to decide whether or not to spend the money to access the mother’s record, hoping that she chose to identify herself and her circumstances.

I’ve never regretted my decision! It is possible to ferret out the clues in these records and identify an actual person and his/her family.

If you have questions, I’d be happy to try to help you navigate the records.

If you have a story idea or a blog that you’d like to share as part of this series, please let us know about it in the comments.