Legacy Tree Genealogists has shared this blog as part of our ongoing “How I Solved It Series” which tells the story about how they were hired for a family research project that led to the discovery of a very interesting court case that solved a tricky brick wall about the parentage of William T. Boykin.

has shared this blog as part of our ongoing “How I Solved It Series” which tells the story about how they were hired for a family research project that led to the discovery of a very interesting court case that solved a tricky brick wall about the parentage of William T. Boykin.

In a recent case we worked on, a dispute over land led to identifying the parents of an individual. We share this story with permission to illustrate the importance of thorough searches – not just in vital records, newspapers, and censuses – but in land, probate, and court records.

Our client asked us to trace the ancestry of his Boykin family, and research had stalled with a direct-line ancestor named William T. Boykin of Southampton County, Virginia, about whom little was known. Our investigation soon turned up a fascinating court case.

In 1816, William was engaged to his first wife, a young woman named Peggy Baisden, who was the only child of her father, Samuel Baisden. As a wedding present to his daughter, Samuel had the local justice of the peace (J.P.), Silas Summerell, draft a deed which granted 100 acres of land to Peggy and her new husband.

It was not long, however, before Samuel Baisden changed his mind about the gift for an unknown reason and wanted the deed back. He appealed first to the J.P., who informed him that it was too late, and that William T. Boykin was now the legal owner of the land. In anger, Samuel Baisden repeatedly threatened his son-in-law with bodily harm and even death for a few years until, out of fear, William finally agreed to give the land back – on one condition. Though William would relinquish his claim on the land, he persuaded his father-in-law to leave the exact same parcel to William and Peggy’s oldest son, Samuel Boykin, as an inheritance when Samuel Baisden died. Witnesses say that Mr. Baisden accepted the bargain and immediately drafted a will to that effect. It seemed that the family drama was over.

During this same time period, Samuel Baisden had remarried to a woman named Lydia, and with her had several more children. When he died in 1824, his will became catalyst to a lawsuit because it was discovered that he had reneged on the earlier agreement and had revised his will to give the 100 acres of land not to his grandson Samuel Boykin, but to his own young son, James Baisden, who had been born in the years since the original conflict and was still only a child. Though he left Peggy Baisden Boykin a few articles of household furniture, she and her children were cut off from the item of real value which they had been promised – the land.

Tragically, Peggy died around the same time in her mid-twenties. On behalf of her and the four children he had with her, William T. Boykin initiated a suit in the county court against his wife’s stepmother, the surviving Lydia Baisden.

While the outcome of this case was not recorded in the court documents we have found so far, the greatest genealogical value came from reading the depositions attached to the case, which unexpectedly enabled us to trace the Boykin line back a further generation. In order to get at the truth of the matter, the county court interviewed several people who were witnesses to the events described in the lawsuit. Among these was the original justice of the peace, Silas Summerell, who was asked to recount his involvement in the granting of the original deed in 1816.

One tiny detail which wasn’t even necessarily relevant made all the difference. Mr. Summerell testified that on the day in question, he had been summoned to the residence of a man named Brittain Boykin, where the Boykin and Baisden families had been gathered to announce the engagement of William and Peggy. It was at Brittain Boykin’s home that the offending deed was originally drafted and signed.

The identity of another deponent in the case was a further clue. This was a man named Solomon Boykin, who spoke in favor of the plaintiff. Previous research had shown that the client’s ancestor, William T. Boykin, had been a witness at the wedding of a Solomon Boykin to Martha Brister in 1819 – only three years after his own marriage to Peggy Baisden. When this fact was combined with knowledge of his participation in the court case, it seemed very likely that Solomon and William were brothers.

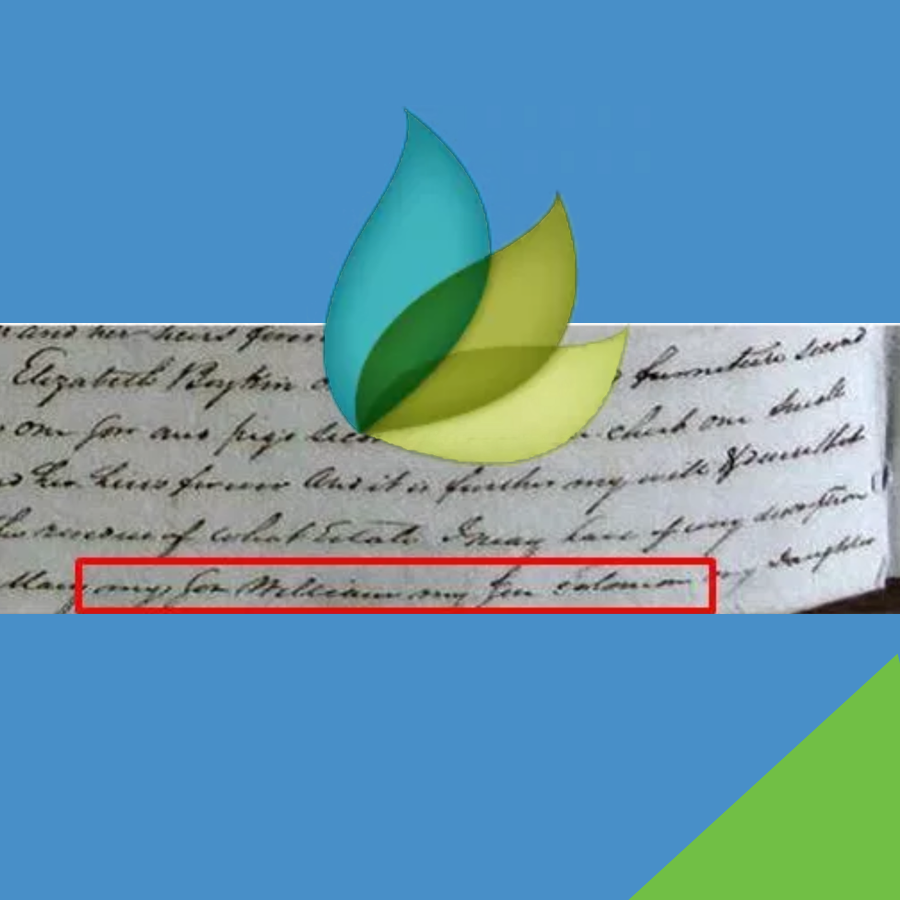

All of these pieces of evidence finally came together when we searched for and found the 1824 will of Brittain Boykin, which named two sons – William and Solomon. Thus, from this thorough approach through land, court, marriage, and probate records, we were able to add another branch to the family tree. On the surface, none of these records alone would have seemed likely to solve the mystery of William’s parentage, but when combined, they provided the needed evidence to connect the individuals.

Could these record types be useful in your own family tree? While probate records are increasingly digitized online (especially at sites like FamilySearch.org), land and court records are overwhelmingly still only found on microfilm and in courthouses. Despite the comparative difficulty in obtaining them, these record types can often be the only thing standing in between answers and a brick wall.

Are you stuck on an ancestor? Don’t have the time to dig as deeply as you’d like? Consider hiring Legacy Tree Genealogists. We have the time and resources to most efficiently address your difficult research problems. Contact them today for a free consultation.

If you have a story idea or a blog that you’d like to share as part of this series, please let us know about it in the comments.