Maggie Stevenson, blog author of Kin Histories, has shared this blog as part of our ongoing “How I Solved It Series”.

Here, discarded artwork leads to the story of a WWI conscientious objector.

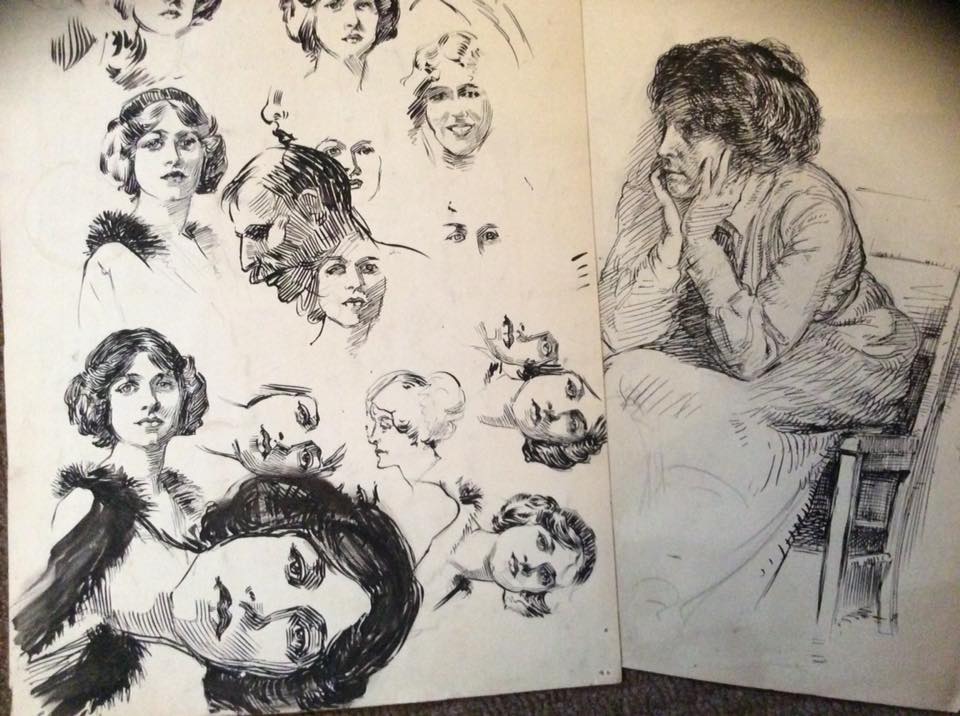

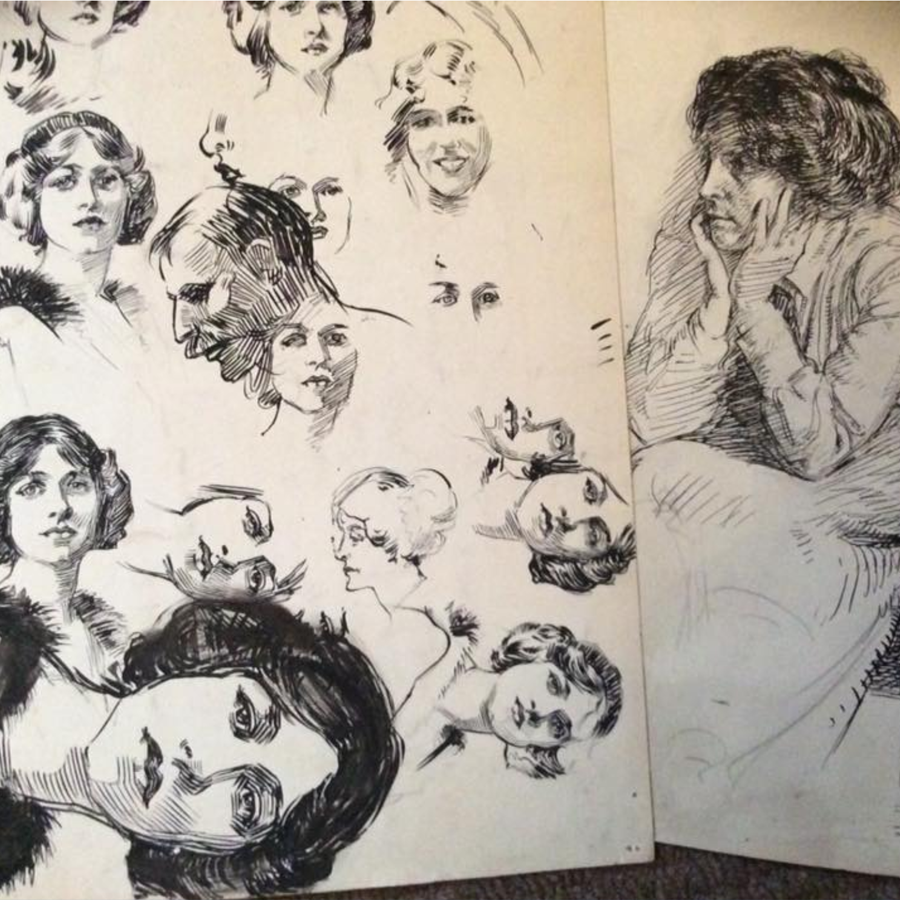

Some years ago a friend was visiting his parents in Nottingham when he noticed a neighbor throwing out an old art portfolio. The sketches were dated from 1909 to 1916, and the neighbor said they were the work of her uncle. He had been an art student at Leicester School of Art. My friend, also an artist, liked the sketches and asked if he could keep them. The neighbor agreed.

About a week ago he posted some of the sketches on Facebook and pondered the fate of this young British artist in World War I. There was no other information to go on other than “G. Noble” and the knowledge that he had been an art student in Leicester around 1910 – 1916.

(Photo courtesy of Ben Morris)

He contacted the De Montfort school in Leicester (previously the Leicester Municipal Technical and Art School) to discover more about the artist. The school had little to go on but was able to provide Ben with a ledger entry. This showed that the student’s name was George Noble and that he paid his student fees in 1913. They also provided a small but significant piece of information (from an unidentified source) that opened up the story of George Noble and highlighted a significant group of men in World War I – the conscientious objectors. Along with another of Ben’s friends, I went through British records from that period and was able to piece together some more of George’s life and what happened to him during the war.

George Noble was born in Hawick in Scotland on 19 May 1885 to Thomas and Jessie Noble. His father Thomas was a hosiery framesmith – someone who knew how to set up and repair the wooden knitting frames used to make stockings. Hawick had a long tradition at the heart of the textile industry. By the time the 1891 census was taken, the family had moved to Leicester, a city in the “Midlands” in England. Thomas was now described as an “engine fitter”. Thomas had been born in Hawick but his father was from Leicester. Perhaps they moved there for better job opportunities and to be closer to family.

In 1901 Thomas Noble’s occupation was clarified as “steam engine fitter” in the census. He presumably constructed, repaired and made replacement parts for steam engines. Son George, now aged 14, was listed as an “apprentice mechanical draftsman”.

By the 1911 UK census George was 25 and still living with his parents and siblings in Leicester, where his occupation was marked as “engineer’s draftsman”.

George may have been studying part-time at art school as his job as an engineer’s draftsman was likely his main focus.

In 1914 World War I started. The UK introduced military conscription in 1916 due to dwindling volunteer forces. Males aged between 18 and 41 had to sign up for service, unless they could already prove they were doing important work. Certain occupations were exempt from active service, including teachers and clergymen. Alongside this exemption, an important right had been built into the Conscription Act. Men had the right to object to conscription on moral or religious grounds.

16000 men tried to claim exemption. George Noble was one of them. The archivist at De Montford was able to provide the following snippet on George Noble:

George Noble…art student, not clear whether he appeared before the Leicester tribunal or in London, but was apparently allowed only an exemption from combatant military service, so was called up to the NCC (Non-combative corp), 6 Northern company, Leicester…

On 29 March 1916 Noble was called before one of the local tribunals. These were set up for conscientious objectors (“CO” for short) to explain their reasons for seeking an exemption from active service. The tribunal panels were made up of local civilians and included an army representative. They may not have been given adequate training or instruction about the task of vetting conscientious objectors. Noble may also have been an “absolutist” – a CO who would not work in any part of the military even if it did not involve combat. Having been granted an exemption from combat, he refused to take up his position in the NCC (the Non-Combative Corp). The NCC was a work-around designed to appease COs whilst fulfilling the military need for recruits. He would not have seen combat in this corp, but would have had to wear uniform and be under army regulations. As a result of his refusal, part of his army record goes on to show that he was arrested and tried at a court martial in Leicester on the 9th of August 1916. Here he was sentenced to 84 days imprisonment “for disobeying a lawful command given by his superior officer.”

Although the harshest sentence that could be meted out by court martial was death by firing squad, there is no evidence that any COs were killed. Several received this sentence but had it commuted. Most conscientious objectors were sent to civil rather than military prisons. George Noble was sent to Welford Road prison in Leicester for part of his detention. His sentence was commuted to 28 days, possibly for “good behavior”. However he was still considered a conscript and would have to make a decision to either continue with the “cat and mouse” cycle of imprisonment that COs often endured, or compromise somehow.

It seems he did choose a compromise rather than return to prison. Several thousand fit young men had been imprisoned in 1916 for refusing to serve. Parliament introduced a scheme that it hoped would help divert some of these men from prison under what was termed “the Home Office Scheme”. Essentially the scheme consisted of a number of work camps with hard labor considered to be “of national importance.” Often this was road building, agricultural labor or menial hospital work. The scheme allowed the men to wear civilian clothing and even to leave the camp for the occasional night out or day off. Various online resources, including the “Men Who Said No” project dedicated to the memory of the COs, note where Noble was sent. He accepted a transfer to a camp at Llanddeusant Water Works in Llangadock, South Wales. Around 200 COs worked there constructing the water works at Llyn Y Fan Fach, Carmarthenshire, to bring a clean water supply to Llanelli. Not a lot has been documented about this particular scheme, and much of the documentation was destroyed after the end of the war. A black and white picture posted on the site of a local archaeology group may show some of the COs in a group shot. They are dressed in “civvies” and flat caps for the most part, armed with only shovels, rakes and sledgehammers. Some of these men possibly stayed with local families for the duration of their “service”. The water works were constructed at over 1600 feet above sea level. The winter weather in particular was likely cold and very wet. Most men who worked on the schemes remained there until April 1919, when all but a few were released.

Without knowing anything more about Noble’s life, we can only wonder about the impact his moral choices had on the rest of his family. Some families were openly scorned and shunned for having a son who refused to go to the front. From other army records we know that George’s younger brother William served in the Post Office Rifles for 2 years before being discharged in 1918 and no longer considered fit for active service. The reason given was “defective vision”. It’s not clear from William’s scrawled, faded army record if he saw active service with this brigade, although it is known that the Post Office Rifles served at both the Battle of the Somme and Ypres. So the Nobles had one son in service and one in prison. Who knows if they supported one but not the other?

Some COs found it hard to secure employment after the war. The only other online record available for George Noble is from the 1939 “register”, a census-like “snapshot” of the adult population of England and Wales taken at the outbreak of WW II. George Noble was living in Leicester with his sister and his mother and was described as a “commercial artist (advertising and printing)”. It seems he was able to continue making a living through art. Ben was told that the Victoria and Albert Museum in London has a poster in its archive designed by him.

The stories of Conscientious Objectors and other opponents of war are now being cataloged by the CO project run by the Peace Pledge Union in the UK.

You can also read more about how COs were treated on the Imperial War Museum website.

http://www.iwm.org.uk/history/conscientious-objectors-in-their-own-words

Thanks to Ben Morris for allowing me to use one of his photographs of the Noble portfolio. And thanks for saving the portfolio!

If you have a story idea or a blog that you’d like to share as part of this series, please let us know about it in the comments.

My name is Judith Noble and I am the Great Niece of George Noble, Conscientious Objector and knew him very well.