Suzi Brent, blog author of Family Tree Mystery, has shared this blog as part of our ongoing “How I Solved It Series”.

Suzi tells the story of how her mother had started the research on Annie. She picked it up to find out what was behind her early death. Newspapers and the inquest being completely reposted solved what happened and also explained why her child ended up where he did.

Annie Catherine Downing 1877-1899

Domestic Servant of Southend, Essex, and my great great grandmother.

My mother actually started tracing the family tree before I did. The person who sparked her interest was her grandfather’s mother. She knew her grandfather, Frederick, had been brought up by his uncle, because his mother had died. She did not know how or when she had died, and had got it into her head that she died in childbirth, though she does not believe that anyone actually told her that explicitly. “These things were not talked about”, she said.

My mother did a bit of digging and found that Frederick’s mother was Annie Downing, who was born in 1877 and was nineteen years old and unmarried at the time of Frederick’s birth. Nine months later, she married Thomas Elsegood. Six weeks after that, she was dead. My mother realised there was clearly more to this story and sent off for Annie’s death certificate, still expecting it to say she died in childbirth, though that of a sibling rather than Frederick himself. What she actually read was a total shock to her:

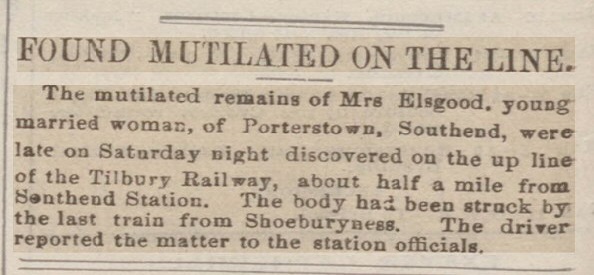

“Cause of death: Did kill herself in front of a certain passenger engine and train upon the line of the London, Tilbury and Southend Railway whereby she was cut to pieces she being at that time in an unsound state of mind”.

Poor Annie! And poor Frederick, losing his mother at such a long age and never knowing his father. What could have happened to make Annie want to kill herself?

This was the point at which my mother lost her genealogy mojo and I took up the gauntlet.

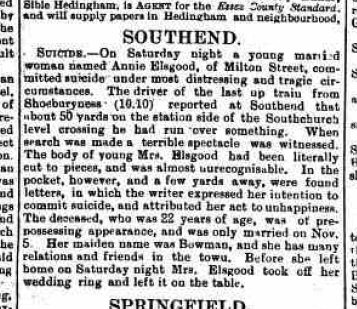

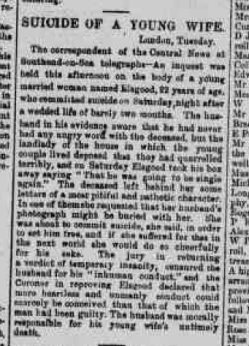

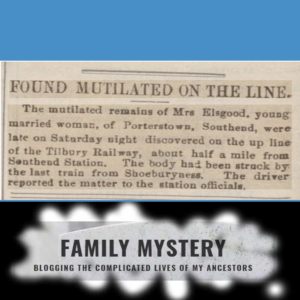

The first thing I found were a few brief articles in local papers on the British Newspaper Archive website, referring to both the incident itself and the inquest.

The incident was obviously big news – it appeared in no less than seventy-three local newspapers available on the site, as far away as Dublin and Dundee. The papers gave some detail into the circumstances of her death: Annie had argued with her husband of six weeks and, believing her marriage to be over already, had gone to the railway line and lain before the last train from Shoeburyness to London.

Why did the prospect of the break up of her marriage push Annie over the edge? Times were different, of course – divorces were only for the rich, being abandoned by your husband was the cause of great shame, and a single woman had few options for work. Annie already had a small child and the stigma of being a single mother would have made life hard enough. Who would want her now? Both her parents had died – her mother three years ago and her father three weeks ago. I wrote before about the devastating effect that the deaths of Henry and Harriet Downing had on their young family. Annie only had her siblings to turn to, but they had their own lives and families. She must have felt very alone and helpless.

You can read about how I found out the identity of Frederick’s father here. The father, Frederick James Allen was from an affluent family and was six years older than Annie. He was a witness at Annie’s older sister’s wedding, so probably a family friend. I suspect that with her mother dead and her father seriously ill and dying, Annie would have looked to Frederick as a way out. As the article above said, Annie was of “pre-possessing appearance” and could have used this to get Frederick Allen where she wanted. If she got pregnant by him, he would have to marry her, and she would be set up for life. But for some reason, Frederick Allen did not want to marry Annie. Five months after Annie’s son was born, Frederick Allen married another woman, Sarah Ann Tate, in Poplar, despite the fact both of them lived in Southend. I wonder if the marriage took place in London to keep it away from the angry Downings?

Annie must have felt so relieved when Tom Elsegood, a local bricklayer, agreed to marry her, despite the fact she already had a child, but maybe she also felt that she was not good enough for him. Unlike Frederick Allen, Tom was not rich, but Annie clearly loved him. She asked to be buried with his photo, and said in her suicide note that she was killing herself in order to set him free.

A couple of years later, I went to Southend Library to look for an article in the Southend Standard about the death of Annie’s brother, Harry. While I was there, I looked at the edition published after Annie’s death, not really expecting to find anything more than what was published in the local papers. But there was a surprise in store. The Southend Standard had published a long and detailed account of the inquest. It made for extremely harrowing reading. As it is so long, I have uploaded it separately here: Southend Standard Inquest Article.

The article talks in detail about Annie’s mental state leading up to her death, making particular reference to her visits to her siblings where she lamented her husband’s cruel treatment of her. She was hungry and distressed. He had referred to her as a “penny prize packet”, continually picked arguments with her over her child, and not given her enough money to eat. Tom, her husband was interrogated at length and denied being cruel to her, but the evidence from their landlady and Annie’s siblings was at odds with this. Annie had left a letter inside a hat at the Brewery Road crossing, now Southchurch Avenue (Google street view here) and I suppose this must be where Annie placed herself in front of the train, though the other articles referenced a level crossing further out of town. Annie’s body (or what remained of it) was found near the Hastings Road level crossing, which has now been replaced with an underpass.

A lot of the text of Annie’s suicide notes – both the note left for her husband and her sister, Lizzie.

I have not got any life left in me. He has completely broken my heart. I never thought I should have to end my life like this, but I shall be at rest, thank God. I could not go out and face the world any more. It has taken the life out of me. The only thing I hope and pray of God is that He may receive my soul so I shall be at rest.

part of Annie’s note to Lizzie

Annie’s note also referenced little Frederick, saying that she had left him at Mrs King’s (her landlady) and that she hoped Alf (her brother) would take him back. The thought of little Fred all on his own with a bewildered Mrs King, wanting his mum and being too young to understand what has happened is quite heartbreaking. Of course, Alf did come and take him back, and that is how my family ended up in Kettering. But more of that another time.

The coroner had the final word towards Tom Elsegood:

You have heard the verdict the jury have returned, and you have probably heard their opinion of you, and that opinion I heartily endorse, for I think a more heartless way, a more unmanly way to have treated a woman could not possibly have been found than that in which you treated her. You may not have struck her, but by your conduct towards her you were the means of driving her to commit this act. It is a terrible thing, and I think it will be a terrible punishment to you to the end of your days. I quite agree with every word the jury has said. You were the person who drove her to do it and you are morally guilty for the cause of her death.

I found this quite interesting – we think of our ancestors as being quite permissive towards the abuse of women, indeed, a Victorian man was generally expected to use physical force to keep his wife in check and the law would only get involved if she was to be seriously injured. Even nowadays, not everyone takes the kind of emotional and financial abuse Tom inflicted on Annie seriously – there is a perception that “real” abuse has to involve physical violence. I was therefore quite surprised to see the severeness of the coroner’s words to Tom Elsegood. Would a modern inquest be so brutal, or would they hold back for fear of being seen as judgemental? Sometimes I feel our ancestors are not quite as backwards as we tend to believe, at least, not in all matters.

Over a century later, I found myself involved with a man who reminds me of Tom Elsegood in many ways – spiteful, dishonest and financially manipulative. But unlike Annie, when my “Tom” left me, I had my house, my job and my pride intact and could fend for myself. There was no shame in being abandoned, no need to find a replacement to keep myself afloat. In that way, I am so much luckier than Annie.

I have visited Annie’s grave – an unmarked plot in North Road burial ground, near to where her mother is buried. The newspaper article says that it was Annie’s wish to be reunited with her mother and for Fred to never know what became over her, and these, at least, were granted. Whether her family also obliged her wish to be buried with Tom’s photo, I am not so sure. In their position, I think I would have burned it!

If you have a story idea or a blog that you’d like to share as part of this series, please let us know about it in the comments.